The email sent will contain a link to this article, the article title, and an article excerpt (if available). For security reasons, your IP address will also be included in the sent email.

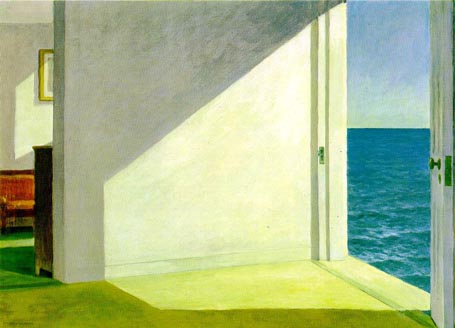

Edward Hopper c. 1951 Rooms by the Sea; image courtesy of Artinvest2000We know what we like when we see it, but don’t always know why we like what we like. In The Architecture of Happiness Alain de Botton ventures a theory to explain this attachment to an object, an artwork, or a building. He writes, “To describe a building as beautiful…suggests more than a mere aesthetic fondness; it implies an attraction to the particular way of life this structure is promoting through its roof, door handles, window frames, staircase and furnishings. A feeling of beauty is a sign that we have come upon a material articulation of certain of our ideas of a good life.” I would amend de Botton’s theory only slightly, to suggest that what we recognize as beautiful taps into our reveries of a desired life, both remembered and anticipated.

Edward Hopper c. 1951 Rooms by the Sea; image courtesy of Artinvest2000We know what we like when we see it, but don’t always know why we like what we like. In The Architecture of Happiness Alain de Botton ventures a theory to explain this attachment to an object, an artwork, or a building. He writes, “To describe a building as beautiful…suggests more than a mere aesthetic fondness; it implies an attraction to the particular way of life this structure is promoting through its roof, door handles, window frames, staircase and furnishings. A feeling of beauty is a sign that we have come upon a material articulation of certain of our ideas of a good life.” I would amend de Botton’s theory only slightly, to suggest that what we recognize as beautiful taps into our reveries of a desired life, both remembered and anticipated.

I have repeatedly found this “material articulation” in paintings, prints, digital montages, and photographs of interiors. The domestic realm as depicted by Pieter de Hooch and Johannes Vermeer in the 17th century, Vilhelm Hammershoi toward the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, Edward Hopper in the mid-century, and Jeffrey Becton, Alanna Fagan, and Abelardo Morell today capture something universal: the dreamy longing we feel for a home of an idealized past rife with imagined possibilities. It's a life full of enticement, prospect, refuge, even hints of potential peril or mystery -- the same characteristics that define the best residential architecture.

de Hooch and Vermeer’s nostalgic anticipation

Pieter de Hooch c. 1658-1660 A Mother and Child with Its Head in Her Lap (A Mother’s Duty); image courtesy of Lines and ColorsIn “A Mother and Child with Its Head in Her Lap (A Mother’s Duty)” c. 1658-1660 Dutch painter Pieter de Hooch sets a layered stage of everyday home life in which the mother and child are almost incidental to the scene. They are busy, faces turned, at nearly middle distance, involved in the child’s grooming in the soft, warm light of a tall window off to the right. Our attention, like that of the dog sitting with its back to us, is drawn past them and the shelter of the built-in bed in the front, tiled room, through the open door and interior side-lite, toward the direct light cast on the floor by the half-open Dutch door washed in daylight, and the transom window above it, to the bucolic realm implied beyond.

Pieter de Hooch c. 1658-1660 A Mother and Child with Its Head in Her Lap (A Mother’s Duty); image courtesy of Lines and ColorsIn “A Mother and Child with Its Head in Her Lap (A Mother’s Duty)” c. 1658-1660 Dutch painter Pieter de Hooch sets a layered stage of everyday home life in which the mother and child are almost incidental to the scene. They are busy, faces turned, at nearly middle distance, involved in the child’s grooming in the soft, warm light of a tall window off to the right. Our attention, like that of the dog sitting with its back to us, is drawn past them and the shelter of the built-in bed in the front, tiled room, through the open door and interior side-lite, toward the direct light cast on the floor by the half-open Dutch door washed in daylight, and the transom window above it, to the bucolic realm implied beyond.

De Hooch invites us to enter a familiar scene, depicting an incidental moment in which a child or an imagined self is cared for, and to pass by, en route to something perhaps more tantalizing and unknown beyond it. Is this a memory or a dream of what may come? Or both?